Himeyuri Students: Education and Ideology Then and Now

Akari Kawasaki

Christina

Abstract:

This website explores the relevance of politics in Japanese education through the example of Himeyuri students. During World War II, Japanese citizens were educated to not surrender to their enemies and instead to ritually sacrifice their lives in honor of their emperor (Emperor Showa) by committing suicide. During this period, many women who were able to work unwed and from the ages of 15 were essentially used in labor forces due to the lack of male workers. Some women were trained as medics likewise the Himeyuri students who were taught to become nurses, attending wounded soldiers inside caves during the Battle of Okinawa. Through the transformation of the educational system, during the Shōwa era, students were taught of the aforementioned ritualistic sacrifice, which led to mass suicides in Okinawa especially towards the end of the war in order to not be captured by the enemy. However, such nationalistic views and ideology still exist in contemporary Japan, as Japanese history textbooks downplay the role of the Japanese military during the Okinawa mass suicides as well as for many other occurrences; these textbooks are still used preventing students from gaining insight into an accurate depiction of history.

Keywords: Himeyuri students, women, education, World War II, Battle of Okinawa

Education in Japan: Prewar, Wartime, and Postwar

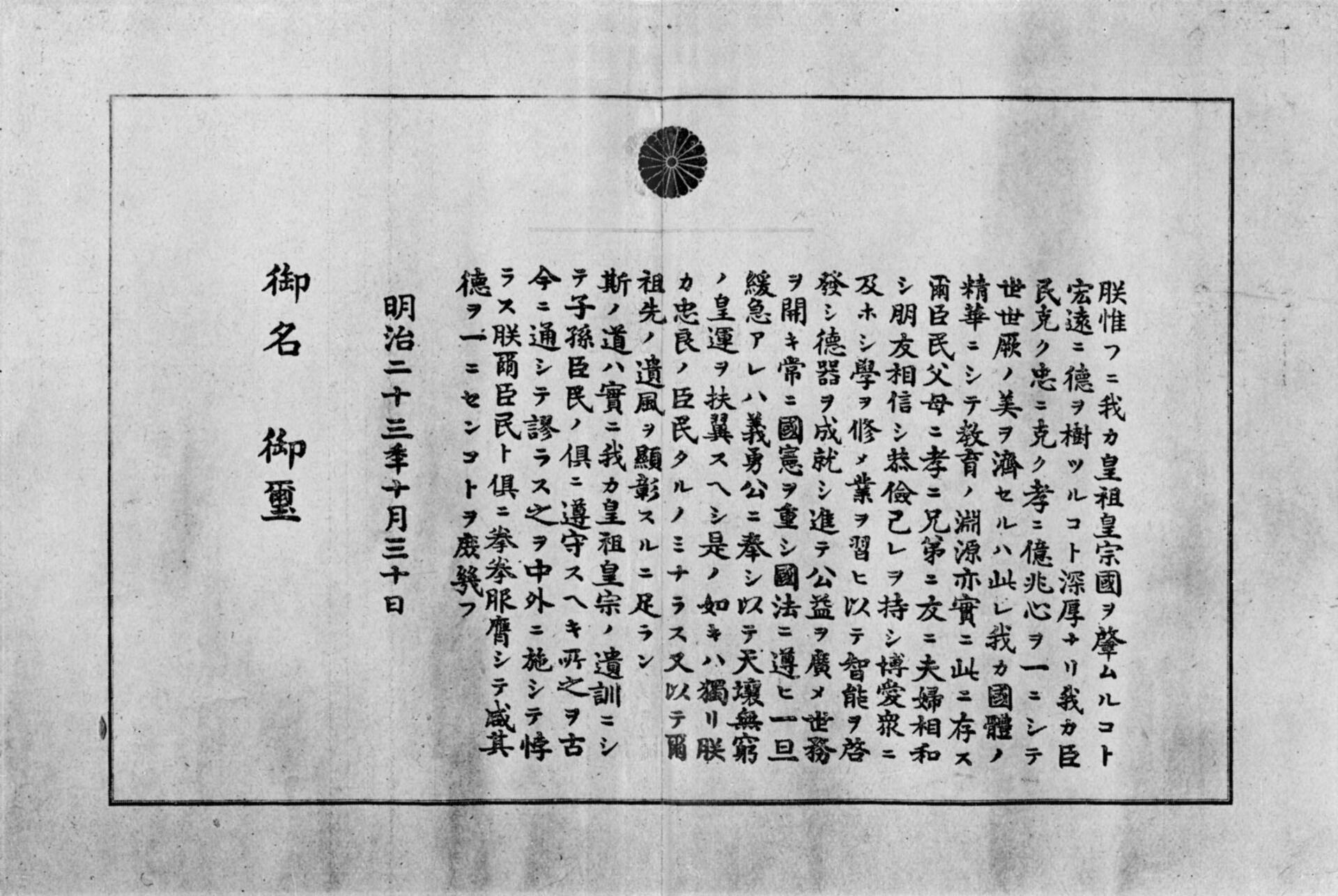

Political ideologies are deeply intertwined with the Japanese education, regardless of the era. Subsequent to the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate that ended the Edo period in 1867, the Meiji era began in which Japan underwent a political revolution known as the Meiji Restoration, often described as a coup d’etat.1 During the 250 years of the Edo period, Japan adopted a strict policy under the Tokugawa Shogunate that kept the country successfully closed from the outside world.2 This meant that trading and contact with foreign countries was controlled by the ruling authorities. However, the succeeding Meiji government commenced to reform their societal institutions including the Japanese educational system due to the arrival of the American Commodore, Matthew Perry’s ships in 1853 during the Edo period exposing a weakness in the Tokugawa regime.34There have been several political and social reforms during the Meiji Restoration; unlike the Tokugawa regime that was ruled by the shogun in which there was nominally an Emperor, the restoration birthed the system of where political sovereignty was given to the Emperor.5 Moreover, during the Tokugawa period, terakoya (translating to temple schools, private elementary education facilities providing children of Japanese commoners how to read and write) were common, however, due to the Westernization and modernization of the Japanese educational system that considered foreign developed countries’ educational systems, the Meiji government promulgated the national system called the Gakusei in 1872.6 Regardless of the reform, both Edo period education and Meiji period education had identical ideologies: traditional Confucianism ethics that highlighted ideas such as duty, loyalty, and nationalism7 (i.e. a sense of identification connecting to patriotism). The Westernization and modernization of the educational institutions led to the promotion of The Imperial Rescript on Education (Kyōiku ni Kansuru Chokugo)8 in public education laying out the expected behaviour from Japanese people while emphasizing the virtues, patriotism, and loyalty to the Emperor (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Kyōiku Chokugo to Gakkō Kyōiku (The Imperial Rescript on Education and school education), 1890. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

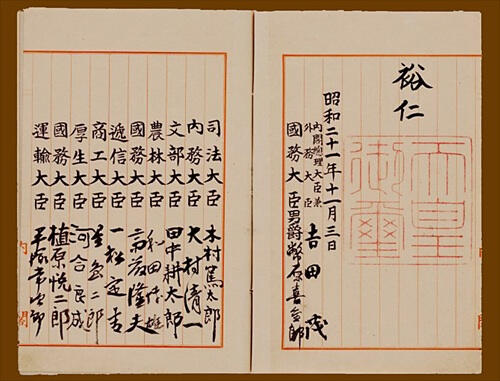

During the Meiji period in Japan, there have been several policies and initiatives implemented to achieve universal primary education for girls. Despite the Ministry of Education issuing a notification in 1872 stating that both boys and girls have the right to receive equal education, in 1879, the Education Order (Kyōikurei) was promulgated directing towards sex-segregated education. The significance of girls’ education moved away from Western egalitarianism and instead towards the Confucianist view of feminine virtues9; nationalist-oriented theories can be seen to have a relevance in the development of girls’ education, implanting a national consciousness of becoming a “good wife and a wise mother”.Political ideologies were more pronounced during wartime periods. Throughout the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and World War II in 1940, militarism and ultra-nationalism10 became more prominent in the Japanese education. Hence, militarist education was reinforced, providing students with textbooks incorporated with ultra-nationalist ideas that were nationally approved. However, after the defeat and surrender to the Allied Forces in 1945, a new Constitution of Japan11 (see figure 2) was promulgated in the following year.12 Hence, there was another educational system reform under the control of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces that suspended Japanese history, geography, and morals textbooks, all of which encouraged militarism.

Figure 2. Signatures of Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru (right) and cabinet ministers on the signing page of the Constitution of Japan, 1946. Image from The Asia-Pacific Journal.

However, Okinawa had undergone different sets of circumstances compared to mainland Japan. During the Meiji Restoration in 1879, the Okinawa Prefecture had been officially absorbed into the Japanese state. However, Okinawans were seen as an inferior ethnic minority, experiencing social stigmas due to their Ryukyuan language and other unfamiliar traits to most of the Yamato race (i.e. the “genuine Japanese”).13 Nevertheless, the recitation of the Imperial Rescript on Education and other rituals of the policy of Kominka (the cultivation of imperial citizens for the state and the Emperor) were imposed upon all children and schools in Okinawa. The policy of Kominka is most clarified in the educational policy for the Okinawan language. Students were strictly forbidden to use the Ryukyuan dialect, receiving the punishment of the “Dialect Placard” if used.14In contemporary Japan, history textbooks have become controversial due to the omission and distortion of mass suicides in Okinawa inflicted by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. Unlike the previous textbook authorization system15, in the current system, textbook examinations are conducted by the Textbook Authorization Research Council (Kyōkayō-tosho Kentei Chōsa Shingikai).16 By distorting the group suicides (shudan jiketsu) that Okinawans had encountered, instead of reconciling the collective memories of Okinawans, it invalidates their experiences.Regardless of the several reforms of the Japanese education throughout the centuries, there is an essence of political interest–by those who have control over the government and authorization–underlying how the educational system is altered.

1. Although there was no mass movement, the bakufu was still overthrown, hence why it is considered a coup d’etat. Wintrobe, “Autocracy and coups d’etat”, p. 127

2. National Institute for Educational Policy Research 2011, p.1

3. This weakness was revealed upon signing the Convention of Kanagawa (1854) and the Harris Treaty (1858) despite believing foreigners were “barbaric”.

4. Wintrobe 2012, p. 126

5. Malcolm, “The Constitution of the Empire of Japan”, p.62

6. Khan, “Schooling Japan’s Imperial subjects in the early ShÔwa period”, p. 216

7. Japan International Cooperation Agency [JICA] 2004, p.17

8. The Imperial Rescript of Education was signed by Emperor Meiji in 1890 to provide a national structure that continues to have a great influence on contemporary Japanese education and society.

9. These sets of values were more conservative that were in accordance with the social customs of the time.

10. Emperor Shōwa (1926–1989) reigned during the military period.

11. This constitution includes the “Fundamental Law of Education” which sets the basis of Japanese education.

12. JICA 2004, p. 22

13. Shibata, “History Education in Japan: An Account of Domestic Policy Controversies Over the Past War”, p. 192–193.

14. There are still implications today due to the imposition.

15. Textbooks have been written and approved by the state.

16. The Textbook Authorization Research Council consists of university professors, schoolteachers, and the Ministry’s examination officers who have experience teaching in higher education.

Women in Labor Forces During World War II

During World War II, the Japanese government mobilized women including female students due to the shortage of men in labor forces. Despite the traditional attitudes17 towards the female labor force, women were nevertheless urged to work in the industry by the Japanese government. However, these industries still continued to prefer male labor, considering the female labor force as temporary help. Due to the divided opinions of the public and the government, some people–like Nakamuda Shinroku,18 a male local leader, believed that despite being educated, a woman's place was at home, serving the country by “keeping their families happy, and producing more future citizens”.19These unmarried women were enlisted to factory service in two stages; the first stage occurred from 1941 to 1943 in which women aged sixteen to twenty-five were working in nonessential industries forming patriotic labor associations such as in textiles, shoes, and pharmaceuticals. The second stage occurred on January 23rd, 1944, when the creation of women’s volunteer labor corps (Joshi Rōdō Teishintai) led women aged twelve to thirty-nine to work in aircraft manufacturing and other essential industries compared to the patriotic labor associations.20

17. The traditional attitudes have been discussed in the prior section.

18. This was implied in his speech in September, 1942.

19. Havens, "Women and War in Japan, 1937–45", p. 920

20. Havens 1975, p. 922

Himeyuri Students

Figure 3. The Himeyuri Students, 1944. Image from book "Ikasarete, Ikite" (Kept Alive and to Live) published by Doyusha.

Okinawa is the only location in Japan that faced land warfare with the United States (U.S.) during World War II and many civilians including women and children from the ages of fourteen were told to serve for their imperial country. This section will focus on the girls from the ages of fifteen to nineteen who trained to nurse the Imperial Japanese Army during the war. They are called the Himeyuri Student Nurse Corps (see figure 3), occasionally called “Lily Corps” in English. In flower symbolism, Lilies have a meaning of "purity" and "dignity", and the "Lily Corps" were asked to become as they were named so. They were a group of 222 students from two schools: Okinawa Daiichi Women’s High School and Okinawa Shihan Women’s School. This excludes the 18 teachers, resulting in a total of 240 people in the Himeyuri Nurse Corps. They were trained and taught how to nurse the wounded soldiers for three months, and did not get education properly during those three months. Himeyuri students were mobilized to hospitals from March 1945 until June which were in small dugouts to hide from the U.S. army.21 The hospitals they were mobilized were small dugouts underground. There were testimonies from students claiming that these dugouts were dark and smelled terrible with the excretions, festers, blood and sweat. In fact, the students experienced hearing screams of patients suffering brain fever, and maggots eating up the wounds.22After June it became clear that Japan will lose the war, so the Himeyuri Nurse Corps were suddenly directed to dissolution, being said that “The Imperial Japanese Army and the school will not hold responsibility, so escape with your own decision”23 and the girls were left by themselves in the middle of Okinawa’s battlefields.Even though they were left out in the dangerous battlefields with bombs dropping like rainfall, they were strongly taught not to be caught by the U.S. army because it is shameful to be captured; students were taught that it is better to die in honour of their family. They were educated that if they get caught and be taken prisoner by their enemies, they will be raped and be run over by tanks naked, and their families will be abused by neighbors by becoming a traitor to the country.24 Therefore, when students heard announcements from the U.S. army claiming that they have food and shelter, many students refused to surrender to them and instead chose to commit suicide.Despite the tragedies, the services of Okinawan girls were introduced in a more heroic tone rather than of a tragic one25; the stories of Himeyuri Nurse Corps were very popular and were read in novels and also watched on films and TV dramas in the 1950s and the 1960s.It is noted in some historical books including Kagawa's Himeyuri tachi no inori – Okinawa no messeiji, that the civilians in Okinawa were killed not only by the U.S. military but also from the soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army.26 It is said by the Okinawans that the soldiers from the Imperial Japanese Army kicked out civilians including children from the civilian’s dugouts and many were dead because the soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army did not protect them, and ordered them to abandon their food and livestock to serve their country.27 In addition, some soldiers in the Imperial Japanese Army killed civilians because the civilians did not speak the same language and saw the Okinawans as enemies.28

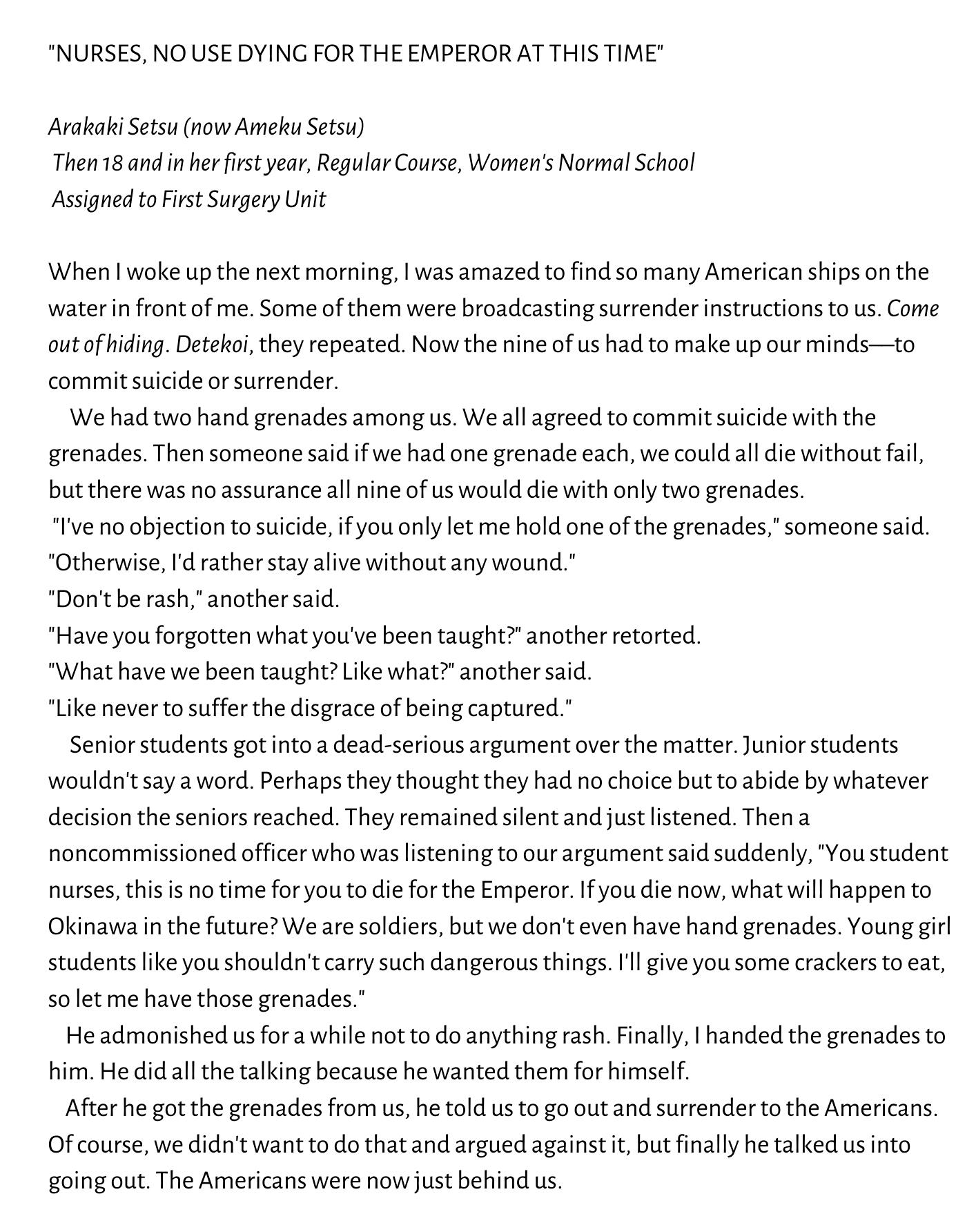

Testimonial from a Himeyuri Student Nurse

Excerpt taken from "Testimonials from Himeyuri Student Nurses", Mānoa 13:1 (2001), p. 149

YouTube Video about the Himeyuri Students

21. Kagawa, "Himeyuri tachi no inori–Okinawa no messēji".

22. Kagawa, 1993.

23. Kagawa 1993, p. 89.

24. Kagawa 1993, p.92.

25. Shibata 2020, p. 195.

26. Shibata 2020, p. 195.

27. Kagawa 1993, p. 98.

28. Shibata 2020, p. 195.

Introduction

While World War II (WWII) created many losses and tragedies, Japanese history textbooks that students use in schools today still indicate strong terms of patriotic and nationalistic ideologies, where its contents have not differed as much comparing them with a textbook centuries ago. War has taken many hopes and dreams from children; the students in the Himeyuri Nurse Corps in Okinawa are one of them. While they were taught to become teachers, their dreams were suddenly taken away and were instead forced to become nurses to take care of wounded soldiers during the wars. This digital exhibition will examine the political ideologies interlinked with the educational reforms in Japan, leading to the mobilization of women in labor forces during WWII, and the disastrous losses including mass suicides of students including those from the Himeyuri Nurse Corps which had been distorted in current Japanese history textbooks.

Contemporary Textbook Controversies

Even after the massive disruption Japan experienced because of the war, the Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe is currently rebuilding the Japanese education system by adding patriotic views in moral education. Abe’s basic speech for his Diet in 2006 was to rewrite the Fundamental Law of Education, rebuilding education, and “nurture people who value their families, their communities and their country”.29 This makes his reform agenda the most assertive since 1947 when the Law of Education was written under U.S. occupation helping to decrease the fascist taste of educational policies in the Imperial era.30 Even with the patriotic agenda, it is still known on a small scale outside of Japan. The Japanese government presents an unofficial translation of the Fundamental Law of Education, which introduced as "We, the people of Japan, desire to further develop the democratic and cultural state we have built through our untiring efforts, and contribute to world peace and the improvement of human welfare"; the original document from 1947 is "Having established the Constitution of Japan, we have shown our resolution to contribute to world peace and human welfare by building a democratic and cultural state". The reformed version has proceeded with a notion of undefined "Japanese-ness" as the amended version starts with the word "we".31 These reforms were strongly welcomed by ultra-nationalist, and a former president of the Japanese Society for Textbook Reform says that Abe's legislation was an acceptance that the liberal education experiment had failed.32

Figure 4. Cartoon lampoons the revision of the Education Law, 2007. Image from The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Despite the many criticisms of the amended education law focused on statements which clearly advantages the state more than the individual. Proclaiming civil liberties existing, but are often disrupted and reduced by new language. With these "nationalistic" and "patriotic" educational laws in the base of Japanese education, recent Japanese education includes these ideology in moral education.

29. McNeill & Lebowitz, “Hammering Down the Educational Nail: Abe Revises the Fundamental law of Education”, p. 1.

30. McNeill and Lebowitz 2007, p. 1.

31. McNeill and Lebowitz 2007, p. 3.

32. McNeill and Lebowit 2007, p. 2.

Conclusion

With the examples focusing on Himeyuri Nurse Corps, this website explored the relevance of politics in Japanese education throughout history, the development of girls’ education in the Meiji period, as well as the policies imposed on Okinawans during the Shōwa period with its implications persisting in contemporary Japanese history textbooks. Moreover, we examine the usage of women in labor forces due to the lack of male workers during WWII and discussed the existence of nationalistic views and ideology that influence today’s Japanese moral education. Despite the tragedies, education remains mostly similar since the war period. It is important for Japanese citizens to reexamine the historical contents taught through the current educational system to their children, bringing reconciliation to those who have suffered during and postwar.

References

Fukuoka Kazuya. “Japanese history textbook controversy at a crossroads?: Joint history research, politicization of textbook adoption process, and apology fatigue in Japan.” Global Change, Peace & Security 30:3 (2018), pp. 313–334. doi:10.1080/14781158.2018.1501012Havens, Thomas. “Women and War in Japan, 1937–45.” The American Historical Review 80:4 (1975), pp. 913–934. doi:10.2307/1867444Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). The history of Japan's educational development. Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2004.Kagawa Kyōko. 香川京子. Himeyuri tachi no inori – Okinawa no messēji ひめゆりたちの祈り – 沖縄のメッセージ. Asahi Shinbun, 1993.Khan, Yoshimitsu. “Schooling Japan’s Imperial subjects in the early ShÔwa period.” History of Education 29:3 (2000), pp.213–223.Malcolm, George Arthur. “The Constitution of the Empire of Japan.” Michigan Law Review 19:1 (1920), pp. 62–72.McNeill, David., & Lebowitz, Adam. “Hammering Down the Educational Nail: Abe Revises the Fundamental law of Education.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 5:7 (2007) pp. 1–8.National Institute for Educational Policy Research. “Education in Japan: Past and Present.” (2011), pp. 1–15.Shibata Masako. “History Education in Japan: An Account of Domestic Policy Controversies Over the Past War.” In Handbook of Education Policy Studies School/University, Curriculum, and Assessment (Vol. 2), ed. Guorui Fan & Thomas Popkewitz, pp. 185–198. Singapore: Springer, 2020.Wintrobe, Ronald. “Autocracy and coups d’etat.” Public Choice 152 (2012), pp. 115–130.